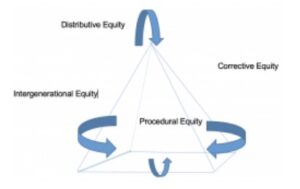

Let’s start by defining what equity means when talking about climate change mitigation.

To understand equity in relation to climate change mitigation planning we can draw from environmental justice frameworks. The publication “Organizing Cools the Planet” found the following common themes in defining climate justice:

“Climate justice is a rights-based framework: It advocates not just for

“Climate justice is a rights-based framework: It advocates not just for

individual liberties, but for collective rights of groups such as Indigenous

peoples and people of color. Justice is central: In this context, justice

means that communities who have suffered at the expense of destructive

economies must not suffer for carbon reductions to occur. Justice is not a

moral obligation alone, but also a pragmatic pathway forward. Climate

justice looks to the big picture transformation of systems, not just the crisis:

Climate justice is underpinned by a long-view approach to social

transformation. While there is no denying that climate change is an urgent

crisis, that urgency must not be used as an excuse to ignore justice

concerns and make unprincipled compromises that harm the most

marginalized communities. “ (Organizing Cools the Planet, 2019)

The social movement Just transition builds on the idea of a rights-based framework to

understand equity in relation to the transition of dirty, extractive, fossil-fuel based economies, to

clean, regenerative economies. The concept began with the intersection of front line environmental justice communities and labor seeking to find common ground and shared benefit in the transition away from polluting industries. Advocacy movements around energy poverty, defined as a household experiencing difficulty affording home energy or transportation, can also support our understanding of accessibility to clean, affordable energy. It is important to note that equity in climate action requires redistribution of resources, providing more resources and opportunities to those that are most marginalized from the system.

What does distributive equity look like when it comes to energy transition?

To meaningfully address inequities through climate change mitigation, tangible policies and

programs focused on marginalized populations are needed, in addition to a strong

understanding of target marginalized communities. Resources and approaches a city might use

to address equity in climate change mitigation depend on the root of historical disparities.

- City staff can work with stakeholders, including members of marginalized communities and community based service providers, to develop a shared agreement on what equity means in the context of mitigation.

- Project developers and governments can utilize Impact Assessments to understand accessibility barriers and opportunities for co-benefits in projects. Income targeted programs and one stop shops can increase accessibility.

- An inclusive engagement process and dedicated resources (honoraria, staffing etc) can be dedicated to engage marginalized communities in the development of climate change mitigation plans. This could include positions in governance structures, such as advisory committees for marginalized populations. Citizen deliberation processes are practiced globally and can ensure that citizens have a say in project development.

- Data is crucial for understanding inequities. Pairing demographic data and energy related data (access, cost etc.) can inform the development of targeted financing and clean energy technology deployment programs. Monitoring and evaluation of programs and projects should also include both qualitative and quantitative metrics that measure equity.

- Targeted funding can be used to finance energy efficiency and clean energy in marginalized communities through financing vehicles such as micro-credit, amortized loans, grants and rebates.

What municipalities are doing a good job of incorporating equity into climate

change mitigation plans and programs?

Climate change mitigation plans generally focus on energy efficiency programs, the deployment

of renewable energy sources, active and public transportation and increased “green

infrastructure” such as trees. While many cities have conducted singular projects that

incorporate equity, most plans only incorporate equity as a passing objective.

Portland is one of the few cities that has incorporated equity considerations into its climate action planning, publishing a Climate Action through Equity plan in 2016. This plan grew out of the Portland Plan, the citywide equity framework, and the Office of Equity and Human Rights. Key aspects of the plan include

- Climate Action Plan Equity Implementation Guide which is used to examine the implementation of 150 Actions in Portland’s Climate Action Plan from the perspective of who programs need to serve, and how regulations distribute the benefits and burdens.

- Portland developed a set of climate equity metrics to track progress on 1) ensuring Portland’s climate actions are more equitable, and 2) furthering equity goals as defined in the Portland Plan through climate actions.

- An engagement plan was developed which aimed to build relationships with diverse communities, and diverse membership within these communities, around climate change.

How is Portland’s plan being implemented at a neighbourhood level

In 2010, a collective effort developed called “Living Cully” focused on Portland’s Cully neighborhood, home to concentrated poverty, racial segregation and environmental burdens. The project aimed to apply sustainability as an anti-poverty strategy to address disparities in education, income, housing and health through concentrated investments in community energy systems. A community energy plan was developed that sought to:

- Identify pilot energy investments that support Living Cully’s anti-displacement strategies

- Advocate for community control of energy investments in Cully

- Provide an energy investment/anti-displacement model for other groups that advocate and organize with low-income people and people of color.

To inform the development of the plan, an in-depth engagement program was conducted in both Spanish and English. Four key investment areas were identified including public education to increase energy literacy, resilient institutions providing spaces for residents post-disaster, provision of affordable & energy efficient housing shielded from market pressures through affordability covenants, and the development of a community energy service to provide renewable energy investments and energy efficiency improvements to low-income homeowners. An important aspect of the plan is the development of social enterprises to employ and train low-income adults, creating contracting opportunities for target businesses.

Three pilots of the community energy plan have been implemented which include:

- An energy education campaign on weatherization skills, energy bill saving strategies and energy efficiency resources conducted through high school curriculum`s, a leadership program, and partnerships with a local university.

- The development of a community complex that contains 150 units of affordable housing market shielded housing, retail spaces, a childcare center and other community-serving uses. The development is incorporating community solar.

- The replacement of 17 mobile homes with new highly Energy Efficient Manufactured Homes-certified units and the construction of a 10kW solar installation on the new community center.

What can we learn from this case study?

To achieve wide-reaching equity impacts in energy transition requires that equity be fully integrated as an objective of a community energy plan, and the implementation of targeted, contextual projects in a community. A central factor of success in Portland was increasing community participation and dialogue through all phases of the project. Having an agenda flexible enough to adjust to the communities’ requirements, allocating specific funding for community engagement, and ensuring the participation of the community-based organizations even after the core process was over, are some of the actions that assure that the community can take ownership of the projects. Some of Portland’s greatest outcomes were driven by the strong focus on the implementation. The Climate Action Plan Equity Implementation Guide proved to be of great value when providing tools for integrating equity.

To achieve wide-reaching equity impacts in energy transition requires that equity be fully integrated as an objective of a community energy plan, and the implementation of targeted, contextual projects in a community. A central factor of success in Portland was increasing community participation and dialogue through all phases of the project. Having an agenda flexible enough to adjust to the communities’ requirements, allocating specific funding for community engagement, and ensuring the participation of the community-based organizations even after the core process was over, are some of the actions that assure that the community can take ownership of the projects. Some of Portland’s greatest outcomes were driven by the strong focus on the implementation. The Climate Action Plan Equity Implementation Guide proved to be of great value when providing tools for integrating equity.

The case study also demonstrates the wide-ranging co-benefits that can be achieved when equity is taken into account and that community-based solutions require integrated approaches. This experience become a catalyst for building capacity not only within the community, but also the city.

Authors: Nelson Nolan & Valeria Rijana

Links:

https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/six-ways-prioritize-equity-energy-efficiency-and-climate-policy

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/state-equity-measurement

https://www.wri.org/research/achieving-social-equity-climate-action

https://energy-cities.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/INNOVATE_guide_FINAL.pdf