Mattia Leone sits on the Coordination Board of the UCCRN – Urban Climate Change Research Network European Hub, being the Scientific responsible for the Climate Resilient Urban Design Workshop series, exploring multi-scale sustainable and resilient urban design strategies through advanced applications of GIS and parametric design tools. Being an Architect holding a PhD in Building Technology and Environmental Design, he is able to work across disciplines while working at the Department of Architecture (DiARC) and at PLINVS-LUPT Study Center at the University of Naples Federico II (UNINA).

We invited him to Barcelona in the light of the increasing collaboration between the two mayor international networks working on urban resilience (the Urban Resilience Research Network – URNet, from where this master and most of the professors come from) and the Urban Climate Change Research Net (similar to the URNet, but specifically addressing climate resilience). What we wish here, as for all our posts, is to share with you what debated in class and the insights from his experience during the 2 days of seminars.

The smart premise of his introduction on urban design and climate resilience was that “We don’t need to “fight” Climate Change. It is just about creating better living conditions for all”, as showed in his very first slide, and wishing thus to avoid explaining a state of the art about climate change, treats, climate data and models “justifying” new transformational urban approaches. “The key issue – he said – is about how to transform our decision-making system, to be able to shift from a command and control thinking, to un-certainty driven decision-making system, becoming the new normal”.

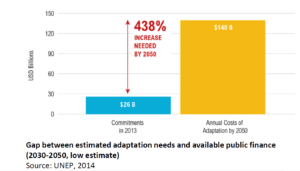

But what does it mean the “uncertainty-driven” decision making? Well, the key objective is to define, design and implement adaptation options able to provide both benefits in the current climate scenario, responding to specific treats, but also enhancing adaptive capacities, strengthening cities and communities’ preparedness and mitigation of future events. Indeed, the notion of “Change” – our behaves, urban services, forms and structures – should not be thought as something critical, happening from time to time to respond to an emergency, but rather a new normal “Modern Design and Governance” mode. “The longer political leaders wait for this paradigm shift, the more expensive adaptation will become and the danger to citizens and the economy will increase”, as shown in the graph below.

While gaps in adaptation investments are huge (as explored also in other seminars, and remarked through Sebastiaan van Herk post available here), there is an increasing need to better link mitigation and adaptation, as a win-win strategy. Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation should, and actually could be better linked, and more integrated strategies should be co-generated with both local and scientific stakeholders, in an inclusive, transparent, participatory, multisectoral, multijurisdictional and interdisciplinary manner. Mattia is therefore calling for an “Adaptive Mitigation Framework” for sustainable and resilient cities, with the aim of being able to deeply transform practices on the ground.

While from one side, research on how to enhance Climate-Sensitive Urban Design has advanced a lot, and is already quite mainstreamed (take a look at the publication here – illustrating how to enhance greening, water sensitive design solutions for rainwater infiltration and potentially retaining and re-use, heat resilient constructions materials, etc.), on the other side, we can clearly see which are the current challenges to shift from solutions-oriented approaches toward a more strategic approach, acting on the urban structure.

Adaptive mitigation design strategies can be implemented in a multiscale perspective – metropolitan region, city, district, block and open space – through a transition to low carbon eco-districts reconfigured based on the local microclimate. Such an approach can effectively contribute to the management of urban drainage modes and the reduction of the heat island effect through the control of key factors guiding strategic choices towards integrated measures.

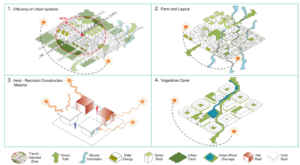

The operational steps to implement urban regeneration interventions in a resilient and climate-adaptive perspective have been defined in the image below, declined through four macro-themes: the first concerning energy efficiency and the reduction of emissions from urban systems through low carbon and near zero solutions; the second looking at the layout of districts to encourage cooling conditions based on the control of solar radiation and ventilation, in order to reduce energy consumption and the impact of high temperatures and intense runoffs. The third principle concerns materials and construction technologies used, both with reference to the stratifications of the envelope and to the surface of buildings and open spaces, while the last parameter concerns the integration of green and blue infrastructures at the different intervention scales, allowing continuity between the peri-urban areas and their possible penetration in the city through networks of parks and green/ blue axes, so as to contribute to the rebalancing of ecosystem services and the increase of biodiversity in urban areas, with significant effects on the health and social equity of the populations living there and of future generations.

Source: Jeffrey Raven (2016). In Raven, J., Stone, B., Mills, G., Towers, J., Katzschner, L., Leone, M., Gaborit, P., Georgescu, M., and Hariri, M. (2018). Urban planning and urban design. In C. Rosenzweig, W. Solecki, P. Romero-Lankao, S. Mehrotra, S. Dhakal, and S. Ali Ibrahim (eds.), Climate Change and Cities: Second Assessment Report of the Urban Climate Change Research Network. Cambridge University Press. (Available at: uccrn.org).

One of the key messages of Mattia, is about the need of bridging hard science – climate modelling and hard data, with urban design toward the urban structure integrated transformation. the first challenge is to ground and situate the climate analysis mapping and modeling. Indeed, once obtaining satellite images and data about surfaces temperature and water stress (for example), it is always better to integrate these information with site surveys, assessing the level of comfort, and considering local behaviors about “acceptable thresholds”, customizing the data from the maps. Mattia showed how in Germany, for example, the threshold for heatwave is around 28-30°C, while in Southern Europe could be over 35°C. In his work, through the UCCRN Climate Resilient Urban Design Workshop series, they co-design and explore how to align computational models with the qualitative and lower scale ones, coming from the real world perceived challenges respect to habits, behaviors, essential functions related to the structure of the city. “You need to start with a Climate Analysis Mapping (from the urban to the local scale), then perform site surveys and finally a public spaces physical evaluation, that will finally inform the planning and design intervention”. Such a complex process explains why UCCRN is also trying to re-frame their way of organizing the dissemination and outreach of their activities, not through big comprehensive reports (you can take a look at them here) and structure the 3rd assessment report as a compendium of Special Reports published with Cambridge University Press Elements Series, and split into the following topics: 1) Urban Climate Science 2) Responding to Shocks and Stresses 3) Informality 4) Governance 5) Big Data and IT 6) Finance 7) Sustainable Consumption and Production 8) Urban Planning and Design 9) Infrastructure 10) Behavior.

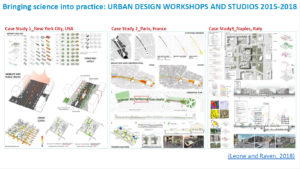

Mattia brought some practical examples from the Urban Climate Lab experience in New York, Paris and Naples.

But let’s share now some details about those practical examples:

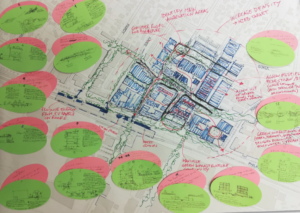

From Naples we could learn how games – yes… games, playing games – could actually support co-design for climate resilience and a deep understanding of the drivers of change and how to adapt design and management strategy at their best. Indeed, the design studio was built on a specific case study and its local priorities (i.e. accessibility, urban agriculture, social services, energy/water/waste and identity challenges). The process that let the group identify those local opportunities was a collaborative mapping exercise (a game) where the participants could play with some cards (related to different kind of solutions/strategies) that would show individual benefits and possible co-benefits. The resilience strategy proposals started addressing those main topics, through solutions integrated within the buildings (solar energy, insulation performances, social services etc.), and in the infrastructure network (dealing with mobility, water/energy decentralization, permeable surfaces and green spaces improvement, as shown below).

New York and Paris design workshops were different, both starting from radiant heat map, building energy performance, ventilation patterns and flood hazard maps. In New York they were able to engage with the City Planning Department, Manhattan Community Board, local architecture firms and the residents. They all worked on an intervention proposal of new urban blocks, public spaces and facilities, looking at new morphology solutions that could integrate a riverside buffer zone, while improving shading, vegetation, walkability and cyclability, through the modification of street orientation and sections. The Paris case was dealing with a new development project, including housing units, commercial spaces and a green corridor, with the integration of urban agriculture dedicated areas, pedestrian and cycling paths, and rainwater collection system. In both case studies, findings from the post-intervention evaluation identified an increase of 20-35% of green cover and a considering decrease in the outdoor temperature.

But not everything is about global north cities. Indeed, Mattia also shared results from a workshop in South Africa – from Isipingo. In this case, the first step was to consider the Durban Climate profile (climate projections and risk assessment), looking at the overlap of the terrain digital elevation model (with buildings) and the flooding projections map, land use composition and heat wave projections. Once on the field, workshop participants identified certain residual stripes of natural corridors that were still contributing to provide important ecosystem services to the area. Thus, the proposed interventions aimed at upgrading the district plan through some climate resilience solutions, as cycling and pedestrian paths provided with trees (providing shade and enhancing microclimate regulation coping with heatwaves), for shading, permeable surfaces for rainwater infiltration and run-off speed decreasing, or street vendors designated areas (enhancing community ties and networking while boosting local informal markets’ activities which previous were on the streets exposed to pollution, insecurity and climate treats). All these proposals emerged through different collaborative and co-design exercises, putting together notes, comments, barriers and ideas into maps (see the picture below).

As you can see from the length and density of this post, Mattia presented to us lots of case studies examples and we had quite interesting in-depth discussions addressing both specific features and generic approaches. One of the final remarks of these discussion was about what we should aim, through climate resilience urban design: not to provide a complete and detailed design solution (to clients or cities), rather the right vision and process to make co-design happen. Indeed, within a complex adaptive system perspective, in which things evolved in an un-expected way, accept the shift toward a design process through which the local authorities, stakeholders, experts from different disciplines, and citizens will be able to own, adapt, and materialize incrementally implement small and structural changes to urban forms and processes. The knowledge is mature, all the information is there and the technology available. What is missing is the capacity to re-think the way city is transformed, which should be not through projects, but processes of co-design and co-management looking to address long term goals. This is now the new challenge: build the conditions that will make the exchange and integration of this knowledge possible.

Images: Mattia Leone

If you want to further explore Mattia’s work, here are some useful links and readings:

- Mattia Leone & Jeffrey Raven, Multi-scale and adaptive-mitigation design methods for climate resilient cities / Metodi progettuali multiscalari e mitigazione adattiva per la resilienza climatica delle città in TECHNE – Journal of Technology for Architecture and Environment, 15, 2018.